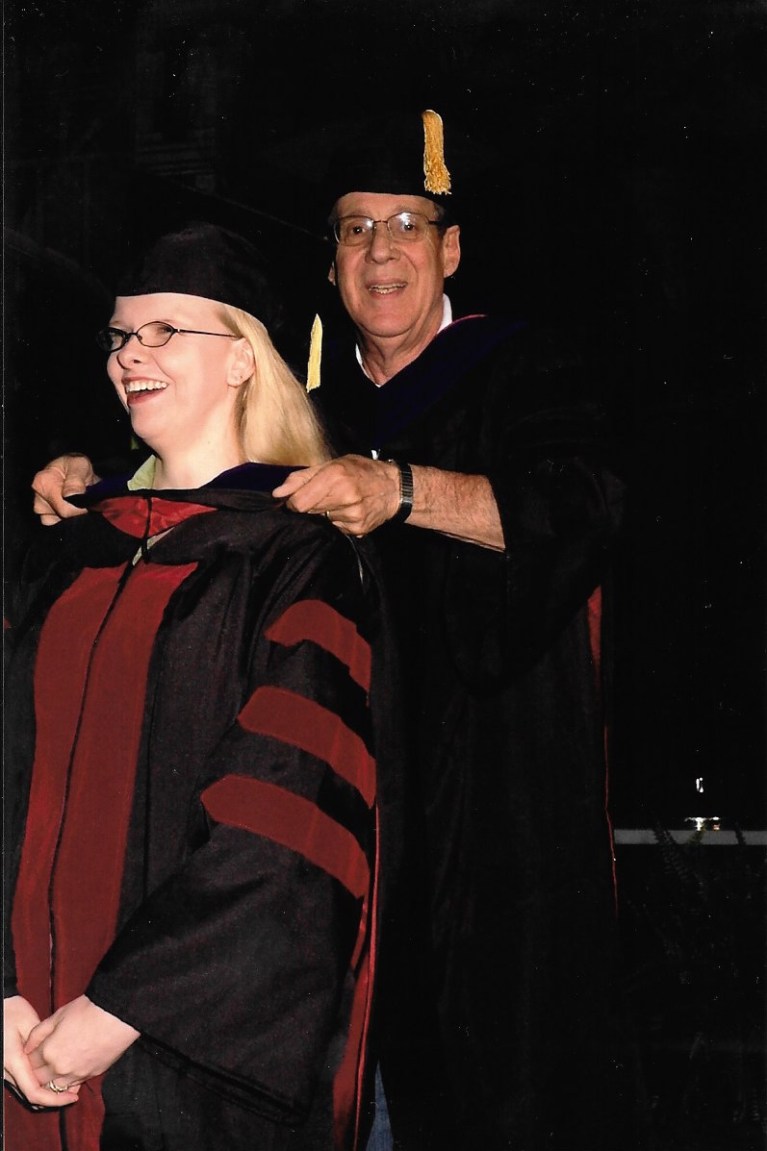

Yesterday, this man, Dr. Bruce A Roe, PhD passed away. Most of you on my feed have no idea who this man is or why I would dedicate this post to him, so give me a minute of your time and I will tell you. Bruce was my major professor for my doctoral degree. He was an amazing scientist and teacher.

He spent his 1978-79 sabbatical in the UK at Fred Sanger’s lab, where he helped develop the renowned Sanger method of DNA sequencing that changed the world of genetics as we know it. He then went on to be a pioneer of that technique here in the USA. Later, he was the first lab to completely sequence a human chromosome, when he published the sequence and analysis of human chromosome 22 in 1999. Even with these amazing accomplishments, I once heard it said of him that his greatest accomplishment was the legacy of his students, and I have to agree.

Bruce was an amazing teacher! It is what attracted me to his lab after taking his Undergraduate Biochemistry corse. He was funny, insightful, and had a way of explaining things that kept you captivated. This was true whether it was in the class room, in the lab, or over a beer in a hot tub… His graduate students and post-docs went forth and created the world of genomics that is before you today, from developing the first kits for dideoxy sequencing to running the top genomics laboratories at places like Wash U. I was lucky to be among the last of his student before he retired.

He taught me the science of DNA sequencing and analysis, but more than that he taught me how to think. It has always stuck with me when he told a group of us student one day that we were not getting a doctor of science, we were getting a doctor of philosophy. The ability to analyze the data was more important than learning the ins and outs of current science, because 50% of what we “know” in science is wrong… we just don’t know which 50%. He saw in me more than I saw in myself; not only the potential as a scientist but to train others to do what I do and fostered that skill. A skill that I utilize everyday to trainer others to be variant scientists like myself at Counsyl.

Thank you Dr. Roe for being my mentor, a father figure, and my friend. I will not morn your passing, but celebrate everything that you gave to all of us lucky enough to receive your teachings. Rest in peace knowing that this world is a better place because you were in it!